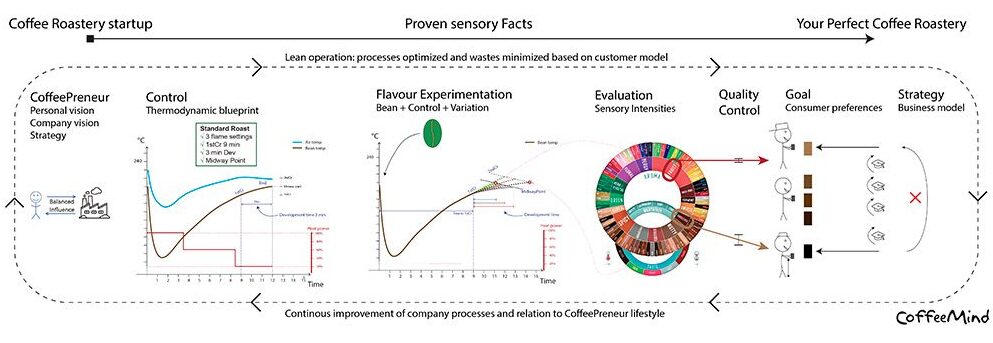

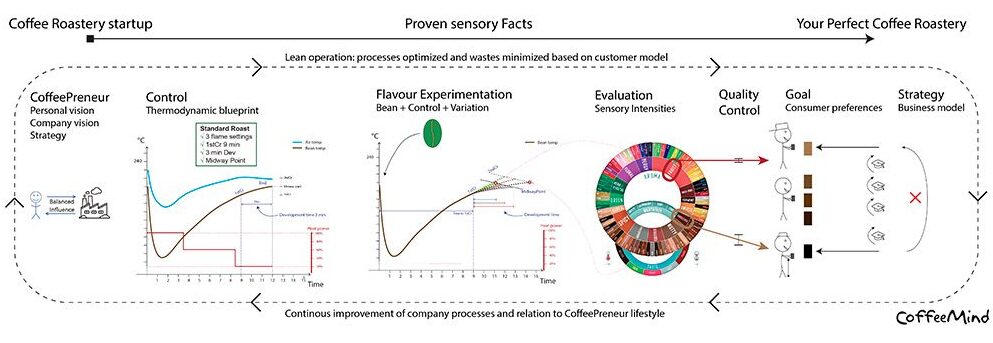

Your Perfect Coffee Roastery: Experimentation – Start with the flavour goal in mind (the customer, even if it is yourself)

Summary

The blog post “Your Perfect Coffee Roastery: Experimentation” highlights the significance of experimenting with coffee roasting. It critiques traditional methods like the 2004 SCA cupping form and Rate of Rise paradigm, suggesting they contradict sensory science principles. It stresses the importance of recognising the diverse flavour preferences among different customer segments and the variability of these preferences over time. The post encourages roasters to focus on the desired flavour outcome and customer satisfaction rather than adhering rigidly to technical guidelines. It advocates for simple, theory-driven experimentation, where only one variable is altered at a time to determine its impact on flavour. The post also critiques the overcomplication of theories in coffee roasting, referencing Occam’s Razor, and calls for an update in traditional methods to better align with modern sensory science, emphasising the need for a nuanced and individualised approach to satisfy varied customer preferences.

Please take a few minutes to think about this question:

- Do you often ask yourself, ‘What is this green bean’s potential? Or ‘how to roast X (X could be ‘Naturals’, ‘Espresso’, ‘Omniroast’)?

If you work aligned with most of the recommendations out there inspired by the 2004 SCA cupping form (which includes the Q-grader system) or the declining Rate of Rise paradigm (see the blog post Why Rate Of Rise Is A Bad Reference Point For Optimizing Flavour In Coffee Roasting) or Development Time Ratio you are working directly against the fundamental principles of sensory science (see this passage from the webinar “The Elements of The Perfect Coffee Roastery” as you are mixing technicalities and preferences under the assumption that there is one – and one only – quality yardstick that we are all chasing (I go deep on this in this podcast episode “Coffee Science methodology Episode 7: The SCA Cupping form”).

Rather than assuming one optimum, we recommend thinking more aligned with our approach, which is aligned with sensory science, where you expect different customer segments to have other preferences, as you can see in the illustration below:

This illustration is slightly exaggerated, with colour-modulating preferences from very old to young people. Still, even inside the speciality coffee community, you will find considerable diversity between preferences. Some people don’t like Pulped natural or Anaerobic coffees that are otherwise praised by others (if you have been anywhere close to a competition or an exhibition since 2020, you would know what we talk about here), or even you have different preferences at different times on the day and across the week! There is no one optimum for anything, so why assume this?

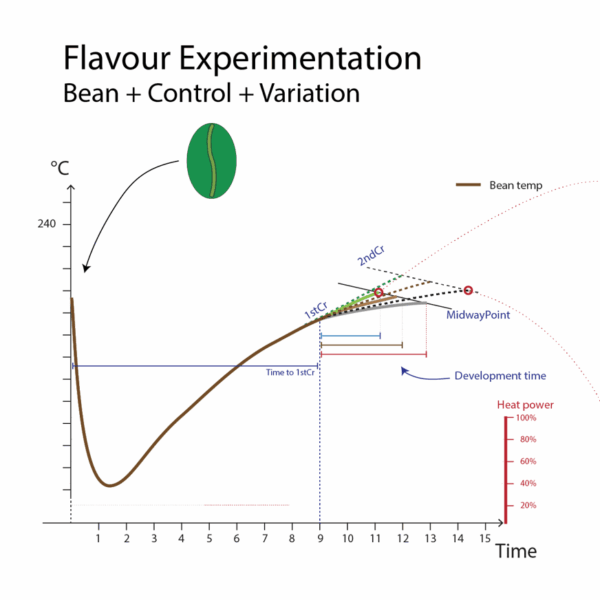

This is where EXPERIMENTATION comes in: You need to let one input parameter (colour, development time, type of bean, or anything like this) change to have a sample set you can evaluate. If you don’t encourage experimentation, you don’t encourage people to think for themselves. Check out this webinar for a deeper explanation: Why would there be one optimum course shape? Or the magical ratio of the development time compared to the total roast time (the development time ratio)?

You need not bury yourself in a rabbit hole and think you can optimise your roast curve by being given guidelines. You need to start with the goal in mind! Who (even if it is yourself, you need to think about what you prefer Saturday morning up against, say, Tuesday afternoon!) do you want to satisfy? And what do you expect them to prefer?

Often, people ask the wrong way around: How do you roast Ethiopian Naturals? How to roast Colombian washed coffee beans. How to roast espresso? How to roast filter? This is starting from the wrong end! You need to ask yourself: Why did I end up with the Ethiopian natural in the first place? What did I hope it brought me in terms of flavours that I could satisfy somebody with (even if it is yourself)? (CoffeeMind’s flavour wheel is designed to help you precisely when you decide on a flavour goal – don’t miss the Podcast episode with the creator of the Flavour wheel, Ida Steen) Why did I end up with the Colombian? One person’s espresso could be somebody else filter. There are no universal categories like that! You need to understand what your customer has in mind with espresso or filter before you can design it to align with it.

Your Perfect Coffee Roastery: Experimentation – Everything else equal

Please take a few minutes to think about these questions:

- How do I set up an experiment correctly so I don’t make false conclusions?

- How do I see whether a claim/theory someone tries to convince you about is qualified or just a good story (Sophism (Plato), Pseudoscience (Karl Popper), Tooth Fairy science)

When setting up an experiment, you decide which question you would like to explore and design samples accordingly so that they are different precisely to the extent that they explore the central question. But here, people often forget to keep everything else equal, which is feature number 6 on the list of features of a scientific theory, as discussed in the first podcast episode of the Coffee Science Methodology podcast series. I often see roasters experiment with drum speed, airflow, start condition and other subtle aspects of the roasting process. When I enquired about colour measurements, they seemed surprised and told me that they did not measure colour because that was not the subject of the study. Suppose you don’t plan your projects with colour consistency between samples. In that case, it will most likely lead to wrong conclusions on the cupping table because the colour difference will be a confounding factor driving the sensory differences on the table and not the more subtle roasting conditions you also changed and thought you were testing. Since you failed to keep ‘everything else equal,’ you have created a mess on the cupping table that can’t answer the fundamental research question you pursued.

For those of you who have not yet listened to the Coffee Science Methodology podcast series, here is a short model of a good theory that is handy for you to use when weeding out old dogmas from applicable theoretical models:

Short description

“A good coffee theory is capturing the most self-critical and simple way of saying something specific about a relevant, expected sensory difference, which is specific in both how the event is created and evaluated and the audience for which the expected difference is expected to be relevant”.

Detailed version

is a longer and more specific list of features of a good theory:

1) Choose simplicity over complexity whenever possible

2) A small cause typically has a negligible effect unless a well-established theory explains otherwise. Expect minor outcome differences from slight differences in input parameters.

3) Form follows function: Design follows purpose. The type of method you choose needs to directly satisfy the purpose of doing the research project in the first place, which is given and specified through the audience for whom the expected difference is both perceivable and relevant.

4) Extremely specific in the description of the circumstances and the setup of the experiment (the input parameters)

5) Extremely specific and narrow in the description of the expected outcome of the experiment as explained by the basic scientific theory underlying the hypothesis of the research project.

6) The everything else equal principle: Only change one input parameter at a time for the different samples and make sure these differences are relevant differences to answer the research question.

7) Has precise concepts for a non-reductionist model relating first-person human experience to the physical/chemical outer world.

7a) For sensory data, keep preference (quality) data and intensity (quantity) data separate!

7b) Any claim of optimum for process parameters must be related to a specified consumer segment and never just justified in a technical aspect.

8) Systematically self-critic when making a possible wrong conclusion due to either personal interest in a particular outcome, confounding factors, or coincidental outcomes.

Your Perfect Coffee Roastery: Experimentation – Make it as simple as possible.

Please take a few minutes to think about these questions.

- Of all the parameters and models you use, are you sure you are not overcomplicating things?

- Do you like things to be overcomplicated? Or do you prefer to use the simplest possible model?

Make sure you use the concepts to formulate your theory and hypothesis with the fewest possible assumptions. If you deviate from this, say by making complicated calculations with hazy assumptions (Rate of Rise, Development time Ratio and so on). You end up managing a system you don’t understand and, hence, find it challenging to use it to solve real problems, such as using your roasting skills to aim for different flavour profiles. Suppose you can’t use your theory and the concepts you use during roasting to navigate flavour from an INTENSITY perspective (how can I make it more or less fruity, more or less acidic, more or less bitter, and so on) and only navigate your roast by a curve shape you can’t make simple EXPERIMENTS. You can see more about this in this webinar at 49:29: Why Rate of Rise is a bad reference point for optimising flavour in coffee roasting.

The first principle I would like to introduce is Occam’s Razor, which urges you to always look for the most simple explanation rather than the most complicated if nothing more is gained by the complication of the explanation. It sounds so simple and accurate, but this single principle is perhaps the most violated in the coffee community as it seems that many people are making a great effort to overcomplicate things rather than simplify things, so it is worth mentioning explicitly and calling out as a separate principle to apply from our historical heritage of scientific methodology.

This is a fundamental approach in the theory of science most widely known as Ockham’s Razor, even though Aristotle already came up with this principle:

“We may assume the superiority of the demonstration which derives from fewer postulates or hypotheses.”

Aristotle (384–322 BC) in Posterior Analytics

And William of Occam says:

“It is futile to do with more things that can be done with fewer.”

William of Ockham (1287–1347 AC) in Summa Totius Logicae

Examples of where this principle is violated in the coffee-roasting community are as follows:

- Most students arrive at my classes strongly focusing on the Rate of Rise rather than just the overall time of different roast events. The RoR is not some hidden root cause for the roasting process that you need to look at independently to understand the roast because it is just a simple derivation of a much simpler aspect, namely the shape of the bean curve that you already see even without calculating and plotting the Rate of Rise. You can use the RoR to predict how the roast will develop in the next few minutes given the current speed, or you can use it to classify different roast profiles on how fast they roast after 1st crack or other simple uses. But claims such as ‘I’m pushing the RoR mountain earlier in this roast’ is equivalent to saying, ‘I push the time to 1st crack earlier in this roast’ and since referring to the simple time to 1st crack is much simpler than to RoR the time to 1st crack is preferred.

- Also, RoR can be reported in deg/15s, deg/30s or deg/min. Given that the roast logger software can optimise its sampling rate independent of how the RoR is reported, it is by far preferred by Occam to be reported in deg/min since this is the simplest expression and easier to use, for example, future predictions of the roast. I have not seen any speedometers in cars using km/5 min or other strange time units that are not directly and intuitively useful by the driver.

- Development time ratio in roasting education is another overcomplicating concept that we will deal with later because it violates many other aspects of a good theory (my central problem with this theory is I don’t know what it predicts). Most of the students I get on my online courses from around the world would tell me the DTR before telling me the time to first crack and development time. Most roast logger software would show you DTR rather than development time, and you must actively change it in the settings if you want to display development time rather than DTR. No wonder newcomers to coffee roasting think DTR is more important than development time… Ockham would prefer to report the roast in minutes for each phase and only when specifically need-derived values can be calculated. For DTR, I don’t know when it would ever be relevant when I see some situations where RoR is useful.

- Defaulting to calculating and using ratios and speeds in all situations rather than just using them only in particular situations where they could be helpful as another built-in problem: You lose information in both types of calculations! If you provide me with the recipe for a brew or show me a roast curve, I could always calculate the ratio, Rate of Rise, or Development Time Ratio myself, but if you give me the ratio, Rate of Rise, or Development Time ratio I can’t go back to the recipe of the brew or the roast course because I have lost information during the calculations of these derivatives. You have the same ratio in a 1-litre brew and a 200ml brew, and you can have different RoR on roast going through the exact same process if the probes are different or placed differently. Likewise, a roast with a total roast time of 10 min and the first crack after 8 min gives you a DTR of 20%, which is also the case for a roast with 20 min total roast time and the first crack at 16 minutes. The fact that you lose information when calculating the speed of a process can be illustrated with mathematics by looking at the technicalities of finding the speed of a power function by applying the power rule, which is beyond the scope of explanation in this oral medium of a podcast, but I have found good explanations on Wikipedia and Kahn academy so please go to the show notes if you want to see how information is lost in the process of deriving the speed of a power function (Wikipedia and Kahn academy)

Your Perfect Coffee Roastery: Experimentation – Plan a sample set of diversity (don’t assume one ‘perfect’ sample)

Take a few minutes to think about this question:

- Do you chase ‘the best’ version of the coffee, or are you aware that there are a lot of different ‘bests’ depending on who you are serving (you yourself might prefer a different roast of the same bean Monday morning vs Saturday afternoon!)

In an experiment, you are deliberately creating diversity in flavour amongst a set of samples so that you, in the next step, where you connect to your customers, can test which version serves the customer segment you are aiming for better (for example – even if this is yourself! – what do you prefer Saturday morning vs Tuesday afternoon).

If you can’t make such a simple experiment, you use overcomplicated, assumption-burdened concepts in your roasting practice.

Unfortunately, one of the major contributors to such a way of thinking is part of the 2004 SCA cupping form (they are improving it these days: https://sca.coffee/value-assessment). The confusion can be addressed from scientific and statistical points of view: It is a preference data collection protocol often presented and used as a descriptive protocol. It is not a descriptive protocol because it focuses on preference data.

Another problem is that the preference data are collected by a small group of people unaware of their preferences related to any possible consumer segment downstream where the coffees are later sold. Suppose the preference analysis does not reflect possible preference differences downstream where the coffees are sold later. In that case, it is not a good model for predicting the preferences of specific customer segments.

For many segments, there might be an opposite relationship between the preferences of a customer segment and the preferences of the few people coming up with a universal cupping score! How often have you not had a coffee rejected by a consumer because ‘The does not taste like coffee – it tastes like fruit juice”? The final cupping score of the SCA cupping protocol is often just the random preferences of a few people (sometimes only one or a few Qgraders) who are elevated to universal heights where they do not belong. It is neither descriptive (would be based on intensities) nor useful from a consumer study perspective, even though most often the data from such an analysis is interpreted as ‘describing the coffees’ and implying to predict that if this one (random) person liked it, it must be ‘good’ and preferred by the general public. Both claims are wrong.

For the community to progress, we should drop this old form altogether and start working with separate methods when we describe intensity differences and map consumer preferences. I have this discussion openly with the Executive Director at SCA’s Coffee Science Foundation, Peter Giuliano, where he acknowledges this problem and talks about what SCA is doing right now to fix it: Coffee Science methodology Episode 12: Peter Giulianos’s feedback. Mixing these two types of descriptors in one method, we get one catastrophe that blurs the picture at such a fundamental level that nobody knows what is going on, and we don’t even have the vocabulary to clarify the discussion and the methods.

The 2004 SCA Cupping form is by far the most problematic single entity created in the sensory realm of speciality coffee when applying fundamental scientific principles of sensory science developed in the 70s, primarily by Rose Marie Pangborn at UC Davis, California. We at CoffeeMind did not come up with this! I, Morten Münchow, was not even born when this was developed. It is time to embrace sensory science’s fundamental distinctions and apply them in our community! We are excited to see how this unfolds with SCA’s new cupping form, which still has a lot of practicalities to be developed before it is useful – read for yourself: https://sca.coffee/value-assessment.

To clarify even more profoundly and focus on the two fundamentally different types of data in the inner world of a sensory-perceiving human being, there are two fundamentally different categories of sensory descriptors: Intensity and Preference. This topic is too long to include in this blog post, but if you want to see how deep this rabbit hole goes, please listen to the podcast where we discuss this comprehensively: Coffee Science methodology Episode 7: The SCA Cupping form.